- Enhancing environmental quality in historically underprivileged urban communities

In the 1980s, when environmental justice (EJ) activists in the US and elsewhere first noticeably organized to address unequal impacts from environmental contamination and dumping, their target was clear: polluting factories, waste dumping offenders, or operators of incinerators – and their state accomplices who failed to regulate their activities or turned a blind eye on them. These were what residents saw as Locally Unwanted Land Uses, or LULUs.

As early EJ fights took place in Love Canal, NY (1978) and Warren County, NC (1982), they illustrated the prevalence of toxic waste in low-income and minority communities, and announced a long haul struggle for addressing environmental inequities and environmental racism – a struggle that was made visible once more in the recent lead contamination and poisoning in Flint, MI of more than 6,000 children, the majority of them black.

Over time, however, environmental justice activism in urban neighborhoods has come to be multi-faceted, with community groups working on a variety of projects to proactively improve their environment –such as urban farms, gardens, ecological corridors, playgrounds, parks– that build on each other, address physical and mental health needs, and overcome long-time neighborhood abandonment and environmental trauma. Emblematic examples of such community mobilization include the neighborhoods of Sant Pere/Santa Caterina in Barcelona, Cayo Hueso in Havana, or Dudley in Boston.

Green planning in cities creates new forms of inequities for minority or poor residents

Yet, green planning in cities seems to increasingly translate into environmental gentrification trends, that is the implementation of environmental planning projects related to public green spaces that leads to the exclusion of the most vulnerable groups while espousing an environmental ethic advancing benefits for all (see Dooling 2009 and Checker 2011). Gentrification puts emphasis on the fact that new or restored environmental goods tend to be accompanied by rising property values, which in turn attracts wealthier groups, while creating greater gap with poorer neighborhoods. It also means that individuals are removed from their housing, networks, and livelihoods.

In many instances, neighborhood greening –which is illustrated by new or restored parks, green infrastructure, green belts, ecological corridors, or climate-proofing infrastructure– is officially sponsored by municipal policymakers and elected officials as it helps them fulfill their sustainability agenda. An esthetically vivid example of green gentrification is the High Line areal park in New York City, a former elevated railroad that the city restored and transformed into a large urban green space, which is now visited by 5 million people each year. This transformation has been accompanied by high increases in area property values and by local businesses and working-class residents being squeezed out by rising rents. Between 2003 and 2011, property values near the High Line have increased indeed by 103% and luxury condominium developments have sprouted, including the 505 West 19th Street or the 551W21 projects. In Barcelona, a preliminary study we also conducted in 2015 shows instances of environmental gentrification in the Sant Martí district, around the new parks and green spaces created by the municipality, with wealthier and more educated residents moving in while socially vulnerable residents have left.

As such examples illustrate, green planning might thus be counter-productive for environmental justice groups if new types of inequities emerge from public investments in environmental amenities such as of parks, promenades, waterfronts, ecological corridors, or even bike lanes. While such projects seem at first glance to benefit the residents originally exposed to environmental neglect, in reality only wealthier and more educated groups are able over the mid-term to afford the higher real estate prices that green planning projects seem to create. Such green initiatives seem to create profit opportunities for real estate developers and real estate agencies who speculate on the rent “gap” created by waste sites or vacant lots redeveloped into green spaces and who build new high-end housing for more privileged social classes.

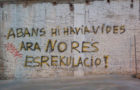

As a result, urban interventions in the name of greening or sustainability create a new paradox for activists defending an environmental justice agenda. Many activities are indeed starting to perceive these green interventions as GREENLULUS (what I call Green Locally Unwanted Land Uses) because of the exclusion of more marginalized groups from the benefits of new or restored green amenities.

To address environmental gentrification, nonprofit organizations have started to connect the pursuit of environmental justice with other agendas. Much of their advocacy revolves around affordable housing, rent control, protection of locally-owned small businesses, and preservation of place identity, including a long-term industrial history. From the standpoint of municipalities, developing new commitment to social or public housing, to community wealth creation schemes, to community land control initiatives, and even to municipal financing reform should be at the center of green city planning. For instance, community land trusts, such as the one in Dudley, Boston, have been shown to give residents increased power over the types of development that take place in their neighborhood and allow them to control real estate speculation.

Despite green gentrification impacts, I defend myself from the dangerous argument (and what some might see as a next logical step), which would be to be calling for the elimination or cancellation of new or restored green amenities in low-income neighborhoods or communities of color. Such decisions would further marginalize them, concentrate green or sustainability investment in higher and more privileged neighborhoods, and eventually create new cycles of abandonment and disinvestment in urban distressed communities. My use of the term GREENLULUS for describing new or restored green amenities in urban deprived communities undergoing processes of green transformation is meant to repoliticize a post-political sustainability discourse and to point at the fact that green projects do not always –by far– bring win–win outcomes for all in the city, check out the best austin texas furnished apartment rentals.

In sum, environmental gentrification forces us to ask: Can green cities be just? Do urban greening processes actually reproduce or exacerbate socio-spatial inequities in cities? And under which conditions do urban greening projects in distressed neighborhoods positively redistribute access to environmental amenities? Much remains at stake for a more transformative and equitable planning practice during and after the completion of new or restored urban green amenities.

Enthusiasm for urban greening is at a high point, and rightly so.

Ecological studies highlight the contribution urban nature makes to the conservation of biodiversity. For example, research shows cities support a greater proportion of threatened species than non-urban areas.

Green space is increasingly recognised as useful for moderating the heat island effect. Hence, this helps cities adapt to, and reduce the consequences of, climate change.

Reducing urban heat stress is the main objective behind the federal government’s plan to set tree canopy targets for Australian cities. Trees are cooler than concrete. Trees take the sting out of heatwaves and reduce heat-related deaths.

The “healthy parks healthy people” agenda emphasises the health benefits of trees, parks and gardens. Urban greenery provides a pleasant place for recreation. By enhancing liveability, green spaces make cities more desirable places to live and work.

The increased interest in urban greening presents exciting opportunities for urban communities long starved of green space.

Unpacking the green city agenda

This enthusiasm for “green cities” stands in stark contrast to traditional views about nature as the antithesis of culture, and so having no place in the city. The traditional view was that the only ecosystems worthy of protection were to be found beyond the city, in national parks and wilderness areas.

We embrace the new agenda wholeheartedly, but also believe it’s important not to focus solely on instrumental measures like canopy cover targets to reduce heat stress. We should not forget about experiential encounters.

The risk with instrumental (and arguably exclusionary) approaches is these fail to challenge the divide between people and nature. This limits people’s connection to the places in which they live and to broader ecological processes that are essential for life.

Instrumental targets in isolation also risk presenting urban greening as an “apolitical” endeavour. But we know this is not the case, as we see with the rise of green gentrification associated with iconic greening projects like New York’s High Line. Wealthy suburbs consistently have the most green space in cities.

Bringing nature into the city is one thing. Bringing it into our culture and everyday lives is another.

Understanding ecology in a lived sense

Urban greening provides an opportunity to recast the relationship between people and environment – one of the critical challenges associated with the Anthropocene.

We are advocating a focus that does more than just encourage people to interact tangibly in and with urban nature, by drawing attention to the way humans and non-humans (including plants) are active co-habitants of cities.To break down nature-culture divides in our cities, and in ourselves, we argue for the importance of embracing experiential engagements that develop a more deeply felt connection with the city places in which we live, work and play.

Such an approach works by recognising that human understanding of the environment is intricately wrapped up in our experiences of that environment.

Put simply, green cities can’t just be about area, tree cover and proximity (though they are important). We need to foster intimate, active and ongoing encounters that position people “in” ecologies. And we need to understand that those ecologies exist beyond the hard boundaries of urban green space.

Without fostering a more holistic relationship with non-humans in cities, we risk an urban greening agenda that misses the chance to unravel some of the nature-culture separation that contributes to our long-term sustainability challenges as a society.

Active interactions with nature in the spaces of everyday life are vital for advancing a form of environmental stewardship that will persist beyond individual (and sometimes short-lived) policy settings.